Universities Should Pay Their Fair Share Too.

Why it’s legitimate to tangle with universities over indirect payments.

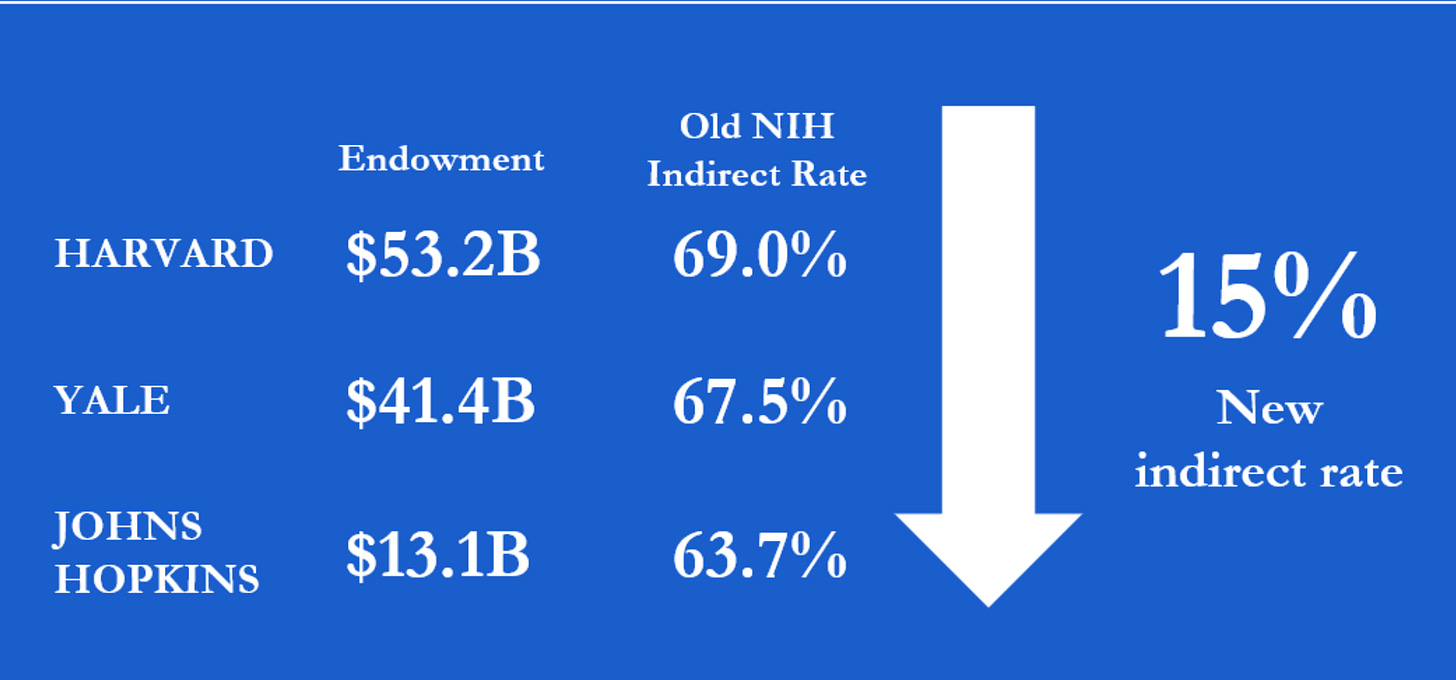

Suddenly, the Trump Administration has reduced the amount the government has been giving to the nations most prestigious research universities by way of an add-on to research contracts. See the chart below: These plus-ups range upwards of sixty percent.

See this post from the NIH Directly: “Last year, $9B of the $35B that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) granted for research was used for administrative overhead, what is known as “indirect costs.” Today, NIH lowered the maximum indirect cost rate research institutions can charge the government to 15%, above what many major foundations allow and much lower than the 60%+ that some institutions charge the government today. This change will save more than $4B a year effective immediately.”

The history of this program is relevant. These “indirect overhead” rates were negotiated by the Department of Health and Human Services on behalf of the NIH back in the 1960s. The justification was that the costs university incurred in administering research grants needed to be recognized and reimbursed.

Importantly, like so much else in government, the justification for this program made sense then, but not so much now. When the subsidy for indirect costs was established, universities were running on shoestrings. They were seen and saw themselves as economically fragile -- dedicated to keeping the cost of a college education affordable. The current enormity of university endowments was an institutional feature far into their futures.

The Trump Administration has appropriately asked universities to put some skin in the game. Among other things, the Administration, working through Elon Musk’s DOGE, appears to have come to understand that if left unscrutinized, universities will use every declared and implicit government subsidy to build glorious buildings and support an enormous corps of administrators.

They will also invent and maintain fashionable academic programs that do not rest on established canons of empirical knowledge and hence offer little in the way of utility to either society or the students recruited into such programs. Majors in critical theory, photography, film making, fashion design, tourism, and entrepreneurship are but a few examples.

Worse, as the recent Harvard and University of North Carolina Supreme Court decisions make clear, universities have embraced practices that are unconstitutional in how they classify applicants and students according to racial identity. Many universities pride themselves on their “work arounds” of the Supreme Court’s ruling, fully intent on continuing programs that illegally favor applicants and community members on the bases of race and gender.

All this brings to mind how as a young professor at Hopkins, I increased the direct support of my research by conspiring to restrict what the university sought to claim as indirect support, then in the neighborhood of 35 percent. Simply, I asked my grant officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to say that it would limit Hopkins’ claim to indirect costs to five percent of the value of the grant. My bet was that the University would not quarrel with a major foundation.

Some years later, when I was CEO of the Kauffman Foundation, an endowment that dispensed about $100 million a year in research funding focused on how to grow economic welfare by encouraging more entrepreneurship, I set a rule that Kauffman would not pay more than five percent to universities to cover overhead costs. Not one university decided not to take our monies. Needless to say, the economists we were supporting were delighted at another example of how markets tend towards efficient solutions.

Mr. Musk and DOGE should examine another implicit federal subsidy, often abused by universities. The Bayh-Dole legislation of 1980 gave intellectual property rights in the findings of federally supported research to the universities where such discoveries were made. On its face, this makes sense given the ineptitude of government officials in bargaining over intellectual property. However, many universities have turned their claim to ownership into formalized employment agreements with faculty, making newly hired professors sign away their rights to ideas that might have commercial value before they have even undertaken the research that might yield such breakthroughs.

Perhaps, given the abuses of the Bayh-Dole program by many universities, it might be time for Musk and DOGE to consider reversing the Bayh-Dole Act and reestablishing the presumption that the federal government is the rightful owner of new ideas for which it has paid. Musk could certainly develop a new federal agency that would be better at managing the transit of innovations and discoveries developed in university labs into practical uses that could contribute to more economic growth for the nation.

Moreover, a consolidated view of the potential product of multiple university laboratories might provide a new perspective on what research to fund going forward. Lest universities find this idea impractical, they might reflect on the extraordinary productivity of corporate labs at companies like GE, AT&T, Boeing, US Steel, and Xerox that gave us multiple Nobel discoveries, all developed in the context of solving problems arising from practical commercial applications.